Every news story that contains a dollar figure is a product of its time, because inflation taints everything. That’s a recurring theme in the book version of Control Your Cash, soon to be released by a major publisher if certain contingencies break the right way.

Inflation, in one paragraph: with rare exceptions, the value of money always decreases. Slowly, but consistently. Right now a dollar is worth about 2% less than it was a year ago. That 2% is fairly consistent throughout the last century. It’d take a few more paragraphs to explain why. Better yet, a future post.

When the dollar amounts get big enough, and a federal government that lost its financial moorings a long time ago starts throwing out 12- and 13- and even 14-digit numbers, you can lose perspective. It’s hard to conceive of a million of anything, let alone a billion or a trillion. Especially when those numbers get bigger every year, thanks in part to inflation.

In the late 1940s, the U.S. dollar replaced the pound sterling as the world’s reserve currency – the default that international transactions are measured in when using another currency would be impractical or confusing. Americans today still benefit from that. Just by virtue of living here, we don’t have to worry about our currency becoming gradually worthless – and our life savings evaporating.

The dollar became the reserve currency largely due to the size of the American economy and the dollar’s relative stability. (It then self-perpetuated: the more stable the dollar, the more firmly entrenched it became as the reserve currency.) But that doesn’t mean it’ll be this way forever. Just this past week, China and several Middle Eastern countries proposed inventing a new currency to supplant the weakening dollar as the denomination in which oil and other commodities should be traded. This new currency would be nothing formal and tradable, just an amalgamation of existing world currencies that aren’t the dollar. That people are taking this seriously shows the dollar is assailable.

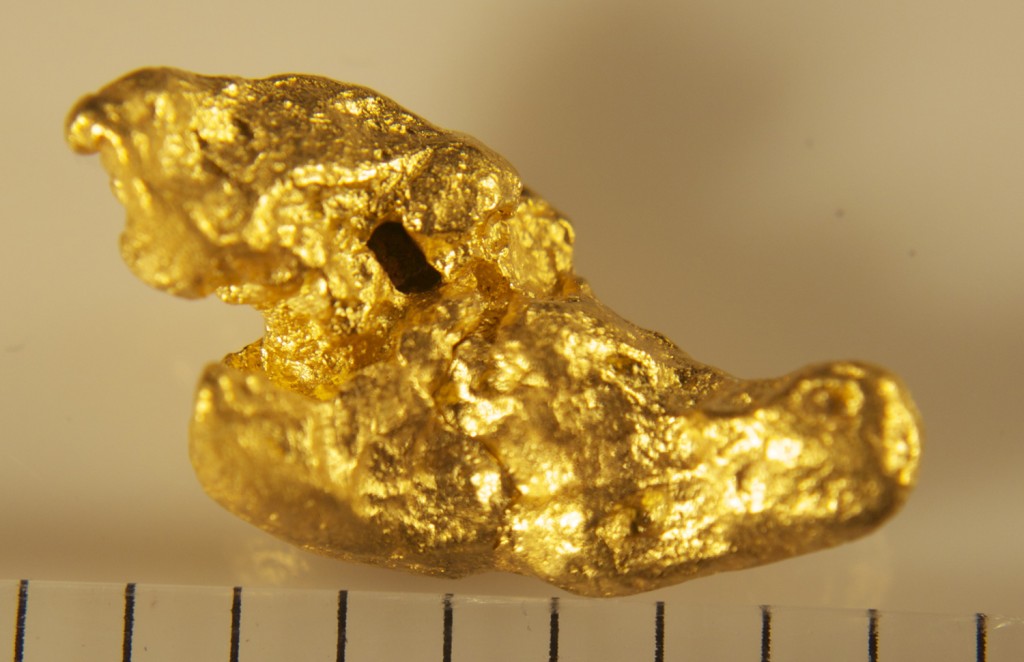

The U.S. dollar has enjoyed a 60-year-and-counting (however tenuously) reign as a powerful medium of exchange. As impressive as that is, gold has served as a store of value for about 100 times longer.

When the government creates too much currency, that currency weakens. Inflates. Becomes less valuable. It’s not hard for this to happen: the government just needs to fire up the presses. When a government owes a lot of money, like the United States’ does, this is an easy way of giving its creditors less than what they really deserve. But, by punishing its creditors, the government also punishes anyone else who does business in dollars. Which would be all Americans.

Gold can’t be injected into the economy as quickly as dollars can. To increase the gold output, you need to find a particularly rich vein, start extracting, put thousands of hours of manpower on the task, refine, purify, separate the dross, and bring it to market. Which is exactly what the world’s gold manufacturers try to do anyway, every day they operate. It’s not easy. That’s why gold, and not cobalt nor nickel, is the historical commodity people have used for money.

Gold isn’t an objective measure of wealth, but it’s as close as we can get in the practical world. Because extra gold is so hard to introduce to the market, gold’s value won’t fluctuate as much as something issued by the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, or the EU. That’s why financial newscasts, publications and websites prominently display the price of gold. When the price of gold goes “up” (you’ll understand the quotation marks in a minute), that’s supposed to represent something noteworthy about both gold’s scarcity and the general state of the economy.

But gold is pretty scarce no matter what. Here’s a semi-rhetorical question: why do we quote gold prices in terms of dollars, a currency continuously weakened by inflation?

Right now, gold is trading at $1049/ounce, “down” $14.90 from yesterday. The Control Your Cash book recommends again and again that in order to greater appreciate how money works, you should examine every financial transaction you engage in from the other party’s perspective. Commodity prices are no exception. Instead of quoting the price of an ounce of gold in dollars, why not say that a dollar is currently trading at 29.65 milligrams of gold (up .41 milligrams from yesterday)?

We propose our own new unit of currency: the gold milligram, symbol Aumg (prounounced “OMG”).

Here are some current exchange rates:

euro 44.18 Aumg

pound sterling 48.15

yen .33

Swiss franc 29.14

Mexican peso 2.26

renminbi 4.34

With no more than two digits before the decimal point, these numbers are easy to visualize. And because of inflation, the numbers will almost all decrease as time passes, reminding the people who use these currencies of their ever-weakening power.

Here are some more for you:

2005 U.S. dollar 73.32

1998 U.S. dollar 109.46

1968 U.S. dollar 883.49

Puts a modest 2% inflation rate into perspective, doesn’t it?

Why should we assume the dollar (or any other state-issued currency) is the objective and constant measure, and gold is the commodity with the wildly variable price? Shouldn’t it be the other way around?

The short answer to the first question is conditioning. Decades ago the United States switched its currency from one defined in terms of gold to one “backed by the full faith and credit of the United States government”, a remnant from the reliquary of charmingly naïve and obsolete buzzphrases.

It’s natural for Americans to phrase their economic thinking in terms of “dollars”. Natural, and convenient, but damaging and incomplete. When a dollar is only as weak or as strong as the Federal Reserve arbitrarily chooses to make it, then the Federal Reserve has the ability to dictate the terms of (and to a large extent, even the size of) the nation’s economy. It’s hard to find a better example of too much power concentrated in the hands of too few. You know, the issue we fought the Brits over.

By one method, the United States money supply increased 6% from 2006 to 2007. That includes not only all the currency in circulation, but all the money held in checking accounts. If a 6% increase sounds modest, consider that the world gold output increased by 1.5% last year. Which triply overstates things, because 2/3 of the gold mined last year was used for industry, jewelry, etc. The 6% figure for the increase in greenbacks is conservative, too. It doesn’t include money in savings accounts, money market accounts, nor certificates of deposit.

In 2006 the Federal Reserve stopped calculating the increase in the broadest possible definition of money; the definition that includes huge institutional certificates of deposit held by banks. (These are CDs worth several hundred times more than the thousand-dollar ones you might be holding. But because they don’t trade among individuals, the government has an excuse for removing them from the equation.) The Fed argued that the costs to collect the data outweighed any benefits, which is why it would no longer estimate how much money is really circulating through the economy.

Yes, a branch of the 21st century American government willfully stopped crunching numbers. Can you think of any scenario in which a branch of the government would do that, if it had nothing to hide? The ironic thing is that the Fed isn’t even hiding what it’s hiding: paraphrasing, they said “Citizen, this information doesn’t concern you, and you wouldn’t know what to do with it anyway. Nothing to see here.”

If the Fed released those numbers, we’d know how many trillions of dollars they’re diluting the economy with. We’d know how few Aumg it’ll take to buy a dollar next year. We’d know how badly inflation is eroding the nest eggs we’ve each spent a lifetime building.

Some estimate that the money supply is really increasing by around 16% annually. Which is more than 30 times faster than the supply of commodity gold is increasing. So which is more stable – the dollar or the Aumg?

The point of this exercise is not to argue that the next time you buy a coffee, you should offer to pay with 40 milligrams of gold. Rather, the point is to put things in perspective when, for instance, Sen. Harry Reid says health care reform will cost 59,301,000,000,000 Aumg. Or 59,301 metric tons of gold. Or 38% of all the gold ever mined.