This week saw the retirement of the kind of American whom Horatio Alger, Jr. used to write books about. Today, that same American could get blamed for everything from childhood obesity to animal cruelty to profiteering off the backs of the downtrodden to increasing income disparity. Here at Control Your Cash, we’ve chosen to find him remarkable. And a shining example of what do to after high school.

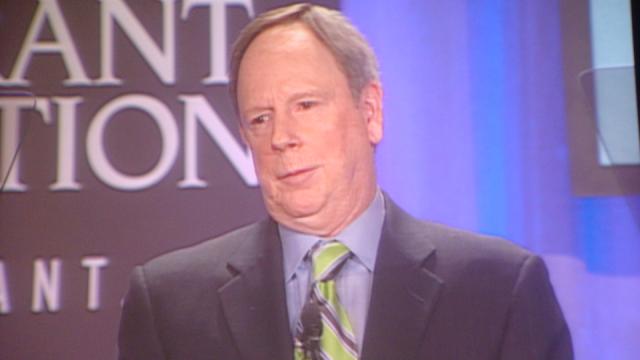

Jim Skinner was one of America’s foremost CEOs. The 67-year old spent 8 years as McDonald’s’ chief executive officer.

Big deal. He took the reins of a company that was already a titan. Any business school graduate could do that.

First, it’s not easy to take over a company that’s supposed to thrive. The downside of such a position vastly outweighs the upside, and if you don’t believe that ask John Sculley (Apple CEO, 1983-1993), Roger Enrico (PepsiCo CEO, 1996-2001), or Antonio Perez (Eastman Kodak CEO, 2005-whenever this bankruptcy finally goes through.) Heck, even Apple’s current CEO Tim Cook is 0-for-1 in presiding over groundbreaking product launches since Steve Jobs’s death. (If there’s an appreciable difference between the resolutions of the iPad 2 and its successor, we can’t see it.)

Phil Jackson coached a record 11 NBA championship teams, and was similarly disregarded for the allegedly failsafe situations he was placed in. If you think it’s easy to coach capricious superstars such as Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant – guys who take sadistic pleasure in exposing and exploiting the weaknesses of their teammates, never mind their opponents – go ask the coaches who were placed in even better situations, the coaches who replaced Jackson himself. The complete list includes Tim Floyd, who finished his career more games under .500 than any coach in NBA history; Rudy Tomjanovich, who lasted barely half a season before quitting; and Mike Brown, who’s presiding over open mutiny as we speak.

Don Thompson, Skinner’s replacement, will need all the help he can get.*

Skinner never graduated from college. He spent 2 years taking night courses at something called Roosevelt University, a private school in Chicago. Its most famous living alumni are former Black Panther Bobby Rush and the guy who plays keyboards for Chicago, the band.

Skinner wasn’t on a regular college schedule, seeing as he had enlisted in the Navy as a teenager. His Navy tenure lasted a decade, and included stints in Vietnam. He saw combat. And returned home at 27 to…flip burgers.

Restaurant management trainee. The kind of job that lots of people scoff at, down to and including many of the baristas and sales associates who make less money per hour than fast-food restaurant managers do. We’re guessing the discipline and responsibility Skinner learned in the Navy meant more to the bosses he answered to on the way up than did anything he learned during his brief tertiary education.

As Skinner himself put it, concerning succeeding generations of management trainees:

They know they have to perform. You don’t get a bye because you walked in off the street and went to Harvard. (New York Times)

Skinner expanded the product line, keeping busybody interest groups and irresponsible parents happy with apples and milk. He slowed down the company’s fanatical growth, concentrating more on expanding profits at the existing stores than colonizing new territories. (Ray Kroc famously said he was in the real estate business, not the food business. Perhaps, but that real estate needs to cash flow.) Skinner even managed to fuse “gourmet coffee” with “McDonald’s” in the public consciousness without anyone laughing.

McDonald’s’ stock price was less than $30 when Skinner took over. Today it’s flirting with $100, and its financial statements are almost perfect: fat profit margins, relatively little debt, growing retained earnings, and tons and tons of treasury stock.

Including everything, Skinner earns about $10 million a year. He still sits on the boards of Walgreens and of Illinois Tool Works. And he owes it all to not spending 4 extra years stagnating in a classroom.

Some of our slower readers will doubtless take the headline literally. Fortunately we no longer have to read their ignorant comments (or anyone else’s, ignorant or otherwise.) Sure, college is great if you use it for its sole purpose – leveraging those 4 (or however many) years so you can make even more money in the subsequent years. Getting a humanities degree isn’t going to do it.

How gauche and philistine of you. College is about expanding one’s horizons, learning for learning’s sake, maturing in an unfamiliar environment, etc.

1. Bullcrap. For most students, college is about getting drunk, sleeping in late, terrorizing the weaker kids in the dorm, wearing togas, vomiting, asking for extensions, making awkward sexual advances, drinking some more, smoking pot, staying up way too late, drinking, vomiting again; and for the exceptionally unattractive and underworked kids, protesting everything from nuclear power plants to U.S. involvement on Johnston Atoll.

2. Fine. It’s all those things you mentioned. You’re right and we’re wrong. College still costs money, in case you thought the millions of people who complain about and default on their loans are just doing so for show. An investment needs some hope of return. Otherwise it’s just an expense.

You’re saving for your own kid’s college tuition right now, aren’t you? Or bankrolling a kid who’s already there, taking English and psychology classes. The Navy doesn’t just give you a better education than Yale’s women, gender, and sexuality program does, it’s also free. Trade school isn’t free, but it’s a lot closer to free than it is to college tuition.

Everyone talks about the benefits of college and dismisses the costs, even though the latter are tangible and the former are not. Jim Skinner knew from an early age to cut through the nonsense. How many of the rest of us are smart enough to do so?

*We kid. Thompson will be fine, even though he went to college. Why? He has an electrical engineering degree (from Purdue.)

This article is featured in: