According to the National Park Service’s website, which no one can access right now due to the governmental shutdown, although they can access the site of the NPS’s parent Department of the Interior for some reason, the U.S. National Parks are owned by the American people.

If “ownership” means determining how the real estate is used, who uses it, and when, then the parks are wholly owned by the federal government and its brownshirts. Some parks have state highways that run through them. For instance, Utah State Highway 9 goes through the heart of Zion National Park, concurrent with the park’s entrance road. The authorities thus can’t very well lock the gates, but the official word is that drivers can’t stop and take photos. Seriously. How they’re going to enforce this is anyone’s guess. Then again, a similar road runs through Yellowstone and last week park rangers stopped a bus full of tourists essentially at gunpoint and ordered the octogenarian tourists on board to proceed without “recreating”. They weren’t even allowed to use the bathrooms. You can look this story up yourself, it’s too nauseating for us to link to. As Mark Steyn points out, if the park rangers had done the same thing to captured al-Qaeda soldiers it would violate the Geneva Conventions.

The people haven’t risen up yet, and probably never will, but at least the bison have something to say about the shutdown:

On with the Carnival:

If you insist on riding the Birth-School-Work-Death treadmill, Justin at Root of Good explains how you can minimize your time in Category III. Spend less and save more. It isn’t much more complicated than that. The only thing we didn’t like about this post is that Justin named the 2 fictional people in his example Sam and Samantha, which is confusing. He should have named them Chris and Kris, or Terry and Terri.

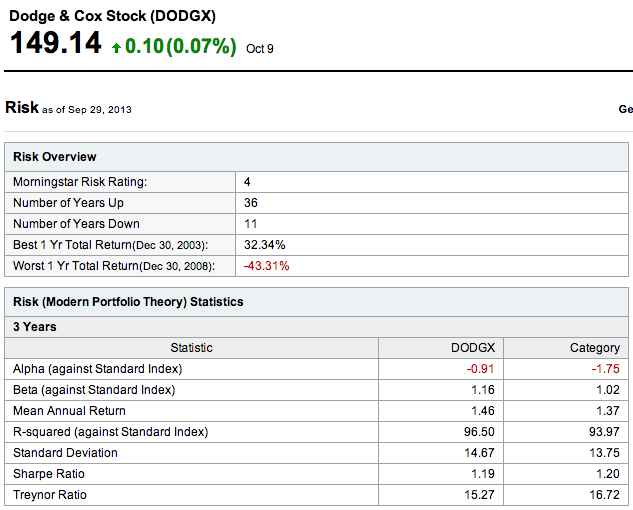

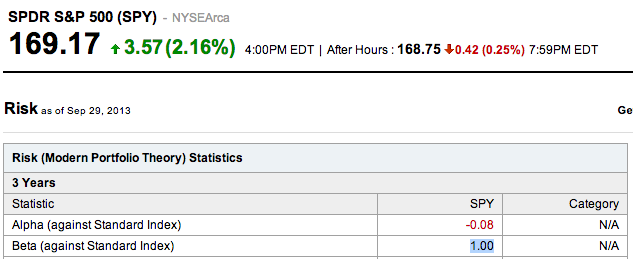

Can you really outperform 70% of fund managers without having any experience? Barbara Friedberg says yes. The detailed answer is yes, assuming you know what asset classes to invest in. Barbara will walk you through the process in several parts, starting with this week’s post.

Paula Pant of Afford Anything just returned from Aruba.

I wish I could go to Aruba! She’s so lucky!

She’s not lucky. She just engineered her life to permit trips to Caribbean islands (and European capitals, and Australian livestock stations, and Indochinese villages.) And as Paula points out, even the most dismal of those is far more enjoyable than wasting one’s life away in a cubicle. She can get you started, assuming you’ve run out of rationalizations not to. We’ll overlook that while the normally infallible Paula cited that Aruba averages 30 traffic deaths a year, she neglected to mention that that makes its streets some of the most dangerous on Earth.

Harry Campbell at The 4 Hour Work Day has a counterargument of sorts. He recently ended a 3-month unemployment hiatus by taking a 9-to-5 gig similar to his old one.

How hard is it to sit behind a desk for 8 hours and browse the internet for part of that time?

Incredibly difficult, if you’re Paula. Less so if you’re Harry.

It would take 3 precious seconds to Google for confirmation, but we’ll attribute to Mark Twain the following quote: “Put all your eggs in one basket, and watch that basket.” Jason at Hull Financial Planning nods his head, making the point that there are times when diversification is a bad idea. Specifically, if you’ve got an aptitude for making money in a particular sector (e.g. residential real estate), use your information advantage to your…well, advantage. Diversification, such as the ultimate diversification of investing in mutual funds, is more about reducing the likelihood of failure than increasing the chance of success. Reinvest in yourself or your business first (assuming you and/or your business are indeed successful.)

Which isn’t to say that mutual funds aren’t for anyone. Otherwise there wouldn’t be $24 trillion invested in them worldwide. Sandi Martin at Spring Personal Finance begins a post series of her own, and reminds the prospective mutual fund buyer that like with a lot of investments, you make your money going in. Management expense ratios vary wildly, from firm to firm and from fund to fund. Paying too big a cut could turn your great returns into modest ones, or your modest ones into losses.

Finally, Cameron Daniels at DQYDJ.net illustrates the net present value of money, and does so without using jargon or even acronyms. Basically what it means is that a bird in the hand really is worth 2 in the bush. Or 1.5 in the bush, or 2.2 in the bush, depending on your tolerance for risk (among other factors.)

No awful submitters this week. Which is to say, no awful submissions. (Hate the sin, not the sinner.) Don’t worry, you can find plenty of those on the Yakezie Carnival. Meanwhile we’ll continue to provide you valuable, entertaining and eclectic content, regularly and frequently. In case you’re unfamiliar with our schedule, we do the CoW every Monday. We do full-length posts every Wednesday and Friday. We do an Anti-Tip of the Day every day, and we reserve our final non-Monday full-length post of each month for the (F)RotM. We use the acronym because we promised we’d play nice, at least temporarily. In related news, we’re now featured weekly on the Stacking Benjamins podcast, available on iTunes and something called Stitcher.

Thanks for coming, and for committing our schedule to memory.