The folks at Go Banking Rates are holding a contest among personal finance bloggers: write a post on the topic of education and wealth, and the lucky winner takes home the Readers’ Choice winner of Favorite PF Blog Writer! (exclamation point theirs.) Thanks to Go Banking Rates for accepting our entry, and may the most interesting and worthwhile post win.

——————

April, 1976. 7-year old me, returning home from school. The teachers had set up a lunchtime hot dog cart. (It was a Catholic school, they raised funds however they could. This predates school-supply drives and the Department of Education.) I eat my lifeless baloney sandwich in silence, jealous of the moneyed kids waiting in line, flashing their quarters like so many engagement rings. Tube steak in a bun, 25¢. And as much as I can remember, my first practical exposure to the idea of money.

Me (trying to determine the family’s net worth in hot dogs): Mom, how much money does Dad make?

Her: (silence)

Me: MOM?!

Her: Don’t you have homework?

And so began a typical North American financial education.

Cannibalism. Atheism. My female teenage cousin’s illegitimate child. In my house, these were just a few of the topics considered more appropriate dinner-table conversation than was money.

Every transaction was a secret. Every dollar figure carried with it the potential for embarrassment. Give a kid even a general idea of his family’s finances, and the next thing you know he’ll be blabbing to the neighbors. We can’t have that. Etiquette should always trump knowledge, shouldn’t it?

1979. I have never read the money section of the newspaper, but the sports section is all mine. Nolan Ryan signs with the Houston Astros for an unprecedented $1 million annually. We have a baseline! My father must make less than that, so…$700,000, maybe? (NB: in his best year he probably made 5% of that.)

To high school. Where the extent of financial instruction consisted of an introductory bookkeeping course, in which we measured the debits and credits of fictional XYZ company and its competitor, ABC company. You know, because terms like “cost of goods sold” and “depreciation” were so relevant to the everyday life of an overloaded teenager who’s already dealing with acne, introduction to beer, football roster cuts, and watching girls’ breasts develop.

14, first job. Washing dishes in a restaurant for minimum wage. Mom exercises her parental right and keeps every check, possibly as partial payment for a lifetime of free room and board.

Fast forward to graduation, and an unsentimental introduction to the real world. Rent? Insurance? 401(k)? IRA? CD? FICA? ARM? S&P? P&L? Drowning in acronyms without a lifeline.

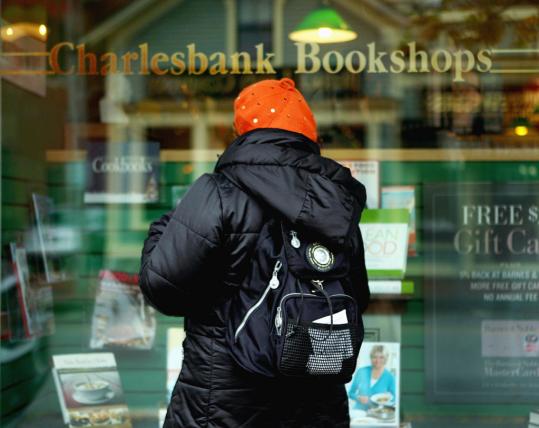

I’m one rung above poverty, which is fine for someone 17 and living on his own for the first time. Wages barely cover necessities, which include a futon and not much else. My one extravagance is books, organized on a bookshelf composed of air. Air, and a floorboard.

And then, those naïve unfortunates at American Express ease the pressure by sending me a credit card I didn’t solicit. The symbolism is overwhelming: plastic signifies my passage into adulthood far more convincingly than any driver’s license or wispy sideburns could. I can buy real furniture! Pick up some new clothes! Dig up the fake ID I’ve been using since the age of 15 and conceivably, rent a car!

Instinctively, I understand that addition is cumulative. A plus B, added to C = A+B+C. It’s one thing to know that in theory, another in practice. Yesterday’s purchase plus this morning’s plus this afternoon’s will look quite different 30 days from now than it does today.

The bill comes. $749.23, which might as well be a quadrillion. The statement contains a caveat that turned out to be a blessing: “PAYMENT MUST BE MADE IN FULL.” I knew this. It was in the agreement I signed and presumably read. No excuses, even though I was a minor.

My right brain tries to convince my left brain that I should become the first person in history to pretend he no longer lives at the address the creditor has on file. An airtight plan that D.B. Cooper himself would be proud of. Fortunately, the left brain wins.

How to get covered? Everyone I know (and who will take my calls) is as poor as me. The right brain thinks about requesting a payment plan, but gets outvoted by reality: a collection letter typed in boldface, immediate interest charges, and the destruction of a nascent credit rating before it even had a chance to grow legs.

Buying a car would have to wait (several years, it turned out.) Same thing for any kind of social life or vacation. A credit counseling company got American Express to take 70 or so cents on the dollar, and I got to start again at zero. Older but still not old, and wiser but still not wise.

What would I change? Nothing and everything (he said in Zen-like fashion.) Nothing, in the sense that I’m grateful that I got the inevitable mistakes out of the way early. Everything, in that sending a young adult out into the world with zero financial knowledge is irresponsible on the part of parents and teachers alike. I might have been one of millions in that situation, but that didn’t make it any easier.

Oh, and parents? Keeping your kids in the dark about finances really helps them out when it comes time to negotiate wages and prices.

It should be effortless to know what things cost – including one’s own labor. No one should have to enter adulthood without knowing the fundamentals of finance – how and where to spend, when and why to invest. If you can understand a savings account, then you can understand a checking account, a money-market account, and ultimately how to buy a car, buy a house, do your taxes and assemble your own S corporation. None of this is that complicated. Our blog proves it.

Epilog: Today, hot dogs cost about $2.69/lb. wholesale. That’s 34¢ a dog, and they retail for at least 79¢, meaning pay a 135% markup or cook your own.