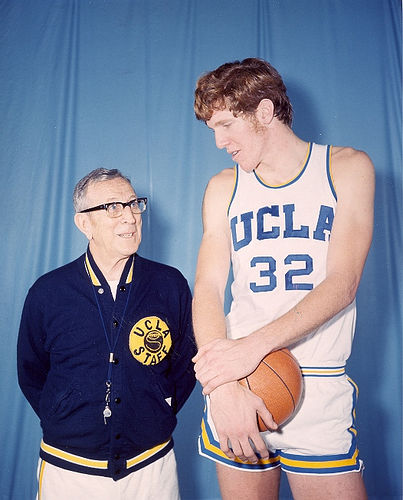

In honor of the late John Wooden, this week’s lesson is to work on your fundamentals.

There are two major ways to evaluate stocks: fundamental analysis and technical analysis.

Groan.

Stop whining. This isn’t difficult.

Fundamental analysis means assessing a company’s financial statements: taking the accountants’ work and reaching conclusions with it.

Technical analysis is the financial equivalent of astrology. It involves looking at how a company’s stock is performing – not how the company itself is performing – and using that to figure out what the stock will do.

Here’s an example of why that’s insane. This is what ExxonMobil stock did from July 3, 2006 to July 20, 2007:

If you remember, public sentiment at the time ran something like:

The oil companies are bleeding us dry!

They’re fixing prices!

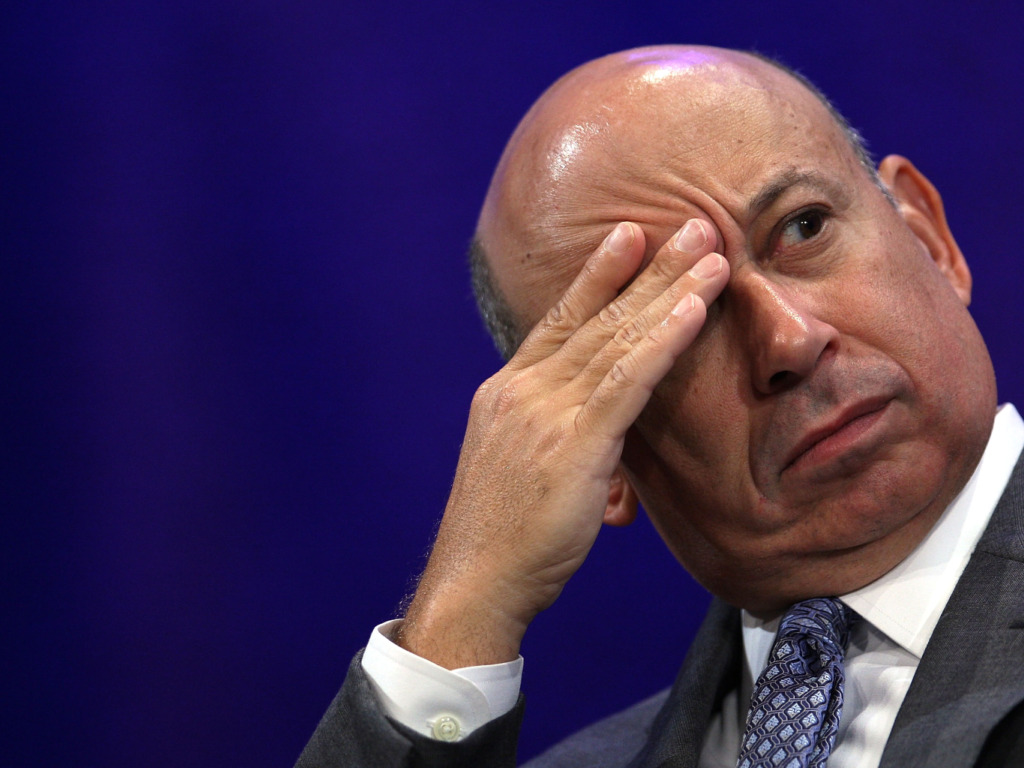

They’re in cahoots with the Bush Administration, the Elders of Zion, the Illuminati and the Trilateral Commission!

What could possibly be a better investment for the short term than a monopolistic, chronic polluter with powerful connections and a product we can’t live without? Any room for me on that gravy train?

Here’s what ExxonMobil has done since then:

The scale on the y-axis changed, but not by much. What happened?

Centrifugal force happened. Public perception brought the stock up to a level it couldn’t sustain. Then reality set in and the stock got too expensive to attract new investors. In July of 2007, a technical analyst would have measured the angle of ExxonMobil’s rise and expected it to continue its northward progress. That same technical analyst wouldn’t reply to your emails today, assuming you could find him.

Most people who offer stock tips advocate some form of technical analysis. Why? Because it’s easy. It takes .12 seconds to comprehend a chart.

You’ve heard the disclosure phrase “past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.” Aside from the inelegant use of the passive voice, the statement makes a lot of sense. When a stock picker uses it to keep things all nice and legal, you have to make a couple of logical connections to deduce the message, which is:

That technical “analysis” we sell? This statement renders it invalid.

Everything is cyclical to some extent, right? No stock consistently outperforms the market, because the numbers don’t allow for it. There’s a ceiling, and it’s lower than you think. If the stock of a company with a market capitalization of $20 million were to double every year, within less than a generation it’d outpace the nation’s gross domestic product.

Fundamental analysis means perusing the unglamorous, dry columns of numbers that accompany corporations’ annual reports. It means going through a few years of data and comparing last year’s net revenue numbers to the previous year’s. Determining whether a company’s net profits increased, or if there’s a good reason why they decreased.

“Picking” a stock in the conventional sense – i.e., figuring out which one is going to suddenly jump in value – is a bigger scam than keno. The established stocks – the Dow components, the companies with the largest revenue and profit numbers – are traditionally the stocks with the strongest likelihood of maintaining their value. But because they’re so big, it’s impossible for them to grow that much more. Any company on this list will probably halve in size before it doubles. For a sports analogy (ladies, I’ll make this as easy as possible), Gordon Beckham (.203) is far more likely to raise his batting average by 50 points than Ichiro Suzuki (.358) is. Market conditions prevent the frontrunners from gaining any significant value. It’s the laggards who make the biggest gains.

And suffer the biggest losses.

Continuing with the analogy, Ichiro’s batting average can afford to move 50 points in the other direction. But if Beckham’s does, he’ll be on either the bench or a bus to Charlotte in short order.

This is another place where we see how badly humanity assesses risk. It’s easy to look at the potential for profit, less so to even acknowledge the possibility of loss. From Gilbert & Sullivan’s Utopia, Limited, the librettist suggests that if you’re going to create a company, begin with a trivial market capitalization. Say, 18p:

You can’t embark on trading too tremendous.

It’s strictly fair, and based on common sense.If you succeed, your profits are stupendous,

And if you fail, pop goes your 18 pence.

A sports analogy, followed by a theater analogy. There, now everything’s in balance.

What’s more likely to hit zero – a company that’s already made its way to consistency, or one that’s closer to being 18 pence away from “popping”?

Of course there’s value in the occasional startup company. If you can find them with any consistency, then please, write this blog for us. You can even rename it after yourself.

And remember: the next coach who tells his team “you need to work on your technicals” will be the first.

**This post is featured in**

The Carnival of Road to Financial Independence #21

and