In a recent Carnival of Wealth we ran a post from someone who wrote:

In an era when the 400 richest Americans account for the same amount of collective wealth as 62% of the nation’s entire population combined and the United States is the fourth most wealth-unequal country in the world, something is grievously wrong with the way income is earned, saved, and distributed.

Yes, every dollar that Dennis Washington earns is ripped from the mouth of a starving welfare baby. The author’s premise is ridiculous, but it resonates with people who still haven’t shaken off the infantile idea of fairness being a supreme attribute in any of its forms. If one person has more, and another has less, that in itself is wrong and subject to correction. Differences in effort, resourcefulness, and refraining from poor decision-making aren’t important. Only the final numbers are.

We can’t quote the author without tripping over the clunky phrase “fourth most wealth-unequal country”, and wonder if being the 195th most wealth-unequal country would be something worth striving for.

When the people at the bottom have a decent standard of living (and in no other country is it better to be poor than the United States), why is what the people at the top make important? Does Donald Trump’s conspicuous consumption – or even a Kardashian’s – impact your or anyone else’s ability to get ahead? Instead of comparing countries, which requires more data than is readily available, let’s compare two subsets of the population with vast differences in their respective income variances: on the one hand, commercial truck drivers and on the other, NBA players.

Here’s what commercial truck drivers make, more or less. We don’t have salary numbers for individuals, given that there are tens of thousands of them, but this is the best we can do:

The seasoned drivers make only 39% more than the rookies, and isn’t that a just and equitable scenario that all of society and by extension all of the world should try to emulate? That the rookies are making barely enough to live on is not our problem. In this example we have fairness, or something close to it.

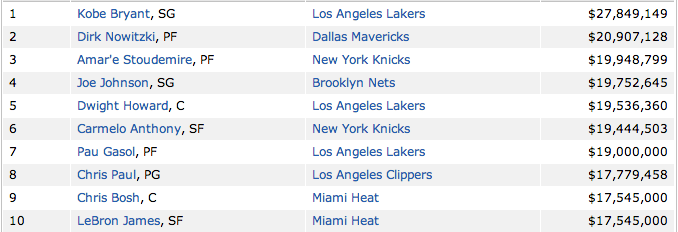

Now, let’s look at what NBA players make. Here are the ten best-paid players in the league. Yes, 8 of them make more than LeBron:

And here are the ten lowest paid players, restricting ourselves to full-timers (guys who have been in the league all year, as opposed to being on 10-day contracts):

They all make league minimum, a number mandated by the league’s collective bargaining agreement.

You see the stinking injustice here? Kobe Bryant makes 59 times what Khris Middleton makes, an obscene state of affairs that’s emblematic of an undeniably American phenomenon, capitalism planting its pivot foot on the throats of the downtrodden.

Khris Middleton makes half a million dollars a year, an amount that almost anyone reading this (and as a group, y’all are not exactly poor) would gladly exchange for her current salary. We don’t know for sure, but we’re also guessing that if you brought up the topic of income inequality to Khris Middleton, he’d either laugh at you or walk away. He’s a bench player who bounces to the D-League and back, while Kobe Bryant has a handful of championship rings and is one of the 8 greatest players who ever lived. The one can make tens of millions of dollars’ difference to his team’s bottom line, while the other is where he is largely due to roster requirements. Fans go out of their way to patronize the former, offering their money as part of the deal. Fans barely know the latter exists. No rational person thinks that this subgroup of the economy should have its workers making identical or nearly identical wages. And no one’s complaining, because the guys at the bottom are doing just fine.

But isn’t it far preferable to have an economy, or a segment of such, in which some people make $13 an hour and others make $18? We’re not qualified to answer: again, you should probably ask the people at the bottom.

Nothing in life is normally distributed. Not athletic ability, not higher-order intelligence, not a capacity for earning money. More importantly, some people enjoy making bad decisions. Look at the poorest of the poor wherever you live (you’ll find them on street corners, drinking MD 20/20 out of paper bags) and ask them if they ever smoked, enjoyed drugs, bought lottery tickets, got neck tattoos, flipped off the boss man, showed up to work late, made the minimum monthly payments on their credit cards, or had kids when they were in no condition to do so.

Now, if you can get past the security guards and high fences, ask the richest people in your town the same thing. Income inequality is a wonderful thing, within reason. (The kind practiced by Kim Jong-Un is a little over the top.) Forget the notion of wealth in our society being “distributed”, like pillows and sleeping bags at camp. Wealth is earned, squandered, built upon, and leveraged. It being “distributed” implies the existence of a Distributor, benevolent or otherwise, whose job it is to see that everyone gets an appropriate share. Which sounds tempting – you don’t have to do anything, just sit there and collect.

One of our favorite quotes about money is by Thomas Sowell. Paraphrasing, he said that if you could wave a magic wand and instantly double everyone’s net worth, some people would be against it because it would increase the gap between rich and poor.