A company is struggling, and the struggle has no quick resolution. (How) can you profit off this situation?

Case in point, and a real-world example. We needed an polyurethane iPad Smart Cover, which is made by Apple and sells for $40. It’s the only accessory we could find that hit the multiple criteria of a) being made especially for the product it’s supposed to accessorize and b) coming from a trusted manufacturer (Apple itself). There are plenty of knockoffs available, but we’re not interested.

While we’re certain the Smart Cover does what it’s supposed to, we still wanted to take a look at it rather than just read the description on Apple.com. So we headed to Best Buy, America’s dominant electronics retailer since the demise of Circuit City. You can touch and play with the iPad Smart Covers there. We did.

Then we bought one on eBay for $23. With free shipping and no sales tax.

Here’s an immutable law of commerce that we’re already seeing regular examples of and will continue to for the next few years: Businesses that operate as showrooms, rather than as businesses, are at a huge disadvantage. Look at the position retailers such as Circuit City and Borders (and now Best Buy, and others to follow) have put themselves in. You can walk in off the street and examine the merchandise at your leisure. The employees range from obsequious to unobtrusive, but none of them are going to give you the hard sell. (Imagine a car dealership operating the same way. More specifically, imagine walking around the floor looking at new models and responding to every salesperson with “No thanks, I’m just looking.” The car dealership would kick you out within minutes. Maybe electronics retailers and bookstores need to place their staff on commission.)

The old business model isn’t just old, it’s counterproductive. Using a retailer/marketplace like Amazon or eBay, plus the wireless provider of your choice, you can walk into Best Buy, look at the items available, buy them from someplace else, then discreetly leave the store. If you really enjoy irony (as distinguished from coincidence), you can buy the items from Amazon or eBay with a phone that you bought at Best Buy. If you’re feeling really daring, you can do it with a floor model display computer.

There’s no obvious solution to this, either, short of Best Buy drastically lowering its prices. Either that or the company could get out of the retail electronics game, and operate exclusively as a seller and installer of large appliances and car stereos. When Best Buy hires us as consultants, that’s what we’ll suggest. Until then, our ideas are merely opinions.

As a customer, your options are plentiful. As an investor, you can make money here: you just have to be resourceful about it. Imagine a market so relatively free that it lets you sell stuff you don’t own.

BBY seems like a perfect example of something worth selling short. This is vastly different than selling a house short. You borrow the stock, hope it loses value, then buy it, then return it to the lender at the original price.

Sound like too much work? Heck, it’s an opportunity. The holder of BBY obviously thinks it’ll appreciate, so it’s only fair that there be a mechanism for profiting off daring him to be wrong.

The compact explanation is as follows. BBY is currently trading at around $20. Say you borrow $20,000 worth of shares, which you can hopefully figure out is 1000 shares. You wait 3 months, and the price has fallen to $16. You then buy $16,000 worth of shares, sell them to the entity you borrowed the original 1000 shares from, and pocket $4,000 (less borrowing charges.)

But instead of following the predicted downward trend for those 3 months, Best Buy gets a patent for a perpetual motion machine. Or finds an oil patch underneath its corporate headquarters (which would be noteworthy, seeing as it’s in a Minneapolis suburb.) The stock shoots up to $60, and the lender wants his 1000 shares back. That’s going to cost you, Ace. $60,000, to put a nice round number on it. You’ll be out $40,000 for your little exercise in semi-sophisticated trading (again, plus borrowing charges.)

What about the actual specifics of short selling? It starts by opening a margin account. E*Trade*, for instance, will let you open a margin account with a minimum balance of $2000 if you already have a regular account with them. When you use a margin account, you’re borrowing E*Trade’s money. You can’t run away from them if you come up short. They know where you live, and they have your money.

So say BBY falls in value, but not by as much as you’d like. After your arbitrary 3-month period, the borrowed money comes due with the stock sitting at $19.53. How much would you make?

This isn’t hard to figure out, and you can probably do it in your head. $470, right?

Go back and read the post again. From the top. E*Trade (or anyone else, other than a particularly dupable family member) is going to charge you interest. Your net profit for that imperceptible decline in the stock price is 0.

Never make an investment without knowing the interest rate you’ll be charged on any money you borrow.

Never make an investment without knowing the interest rate you’ll be charged on any money you borrow.

Never make an investment without knowing the interest rate you’ll be charged on any money you borrow.

Should we say it once more, underlining this time, or did you get the message?

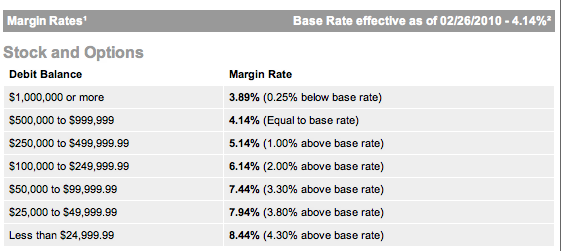

Brokerages start with something called the “base rate”. E*Trade set its at 4.14% a couple of years ago, and it’s remained untouched since. If you have half a million dollars in your margin account, you get to borrow money at the base rate. (Put a million in your account, and they’ll take 25 basis points off the base rate.) But the less your ability to repay, the higher the interest rate you’re charged. That’s why unsecured credit cards charge so much, which you shouldn’t be paying interest on anyway. With that $2000 minimum balance in your margin account, you’ll pay a 430-basis-point premium on the money you borrow. 8.44%. You’re almost better off borrowing on that credit card. Almost. Here’s the list of interest rates, segmented by size of account balance:

Making money’s a pain, isn’t it? For a beginning-to-intermediate investor, better to find something undervalued and buy it long than search for something overvalued. The worst thing that a stock you perceive to be undervalued can do is fall to 0. A stock that you think is overvalued, but isn’t, can rise so high that you’ll lose your margin account, your house, your 401(k) and the respect of your friends and family. Now, who’s up for some trading?

*Technically, the name is supposed to be in all caps. They should consider themselves fortunate that we’re deigning to indulge even one of their typographic fantasies by spelling the company name with an asterisk. The asterisked name spawned an asterisked comment, adding to the confusion, a confusion that this asterisked comment can’t hope to resolve.