Control Your Cash Trivia Time!

Which will lubelessly rape your wallet the fastest while leaving the deepest scars?

- Incurring credit card debt

- Having children

- Going to a car dealer for repairs and parts

The answer is 2, of course, but that doesn’t make for as interesting a blog post as if we assume the answer is 3.

What turns most people off about personal finance is that so much of it is about economization. Go without, deny yourself one of life’s immediate pleasures, and maybe in the future you can enjoy a slightly greater pleasure. No wonder so many people just give up and decide to indulge themselves immediately.

But this is different. Here at Control Your Cash we consistently urge you to make painless choices that you won’t even notice after you’ve spent the initial few seconds making them.

Like the idiots we see waiting in the drive-through lane at Starbucks every morning. Yes, the “latte factor” has been analyzed to death already, but it’s still valid. These people not only pay 2000% markup for the privilege of patronizing Starbucks, they wait in line longer than it would take for them to brew their own coffee. So they’re not even purchasing convenience, however much that’s worth. They’re wasting money simply out of habit.

Log into your car insurance account, and your health insurance account while you’re at it, and check your limits. You’re probably overcovered, and throwing money away each month unnecessarily. Once you reduce your limits, you won’t be suffering through the privation of having reduced coverage. You’ll be saving more money, again with minimal effort, and all for a few minutes’ work. We’re not talking about forgoing that Fijian vacation you’ve been working towards and desperately wanting for so long. We’re talking about doing practically nothing and getting more money out of it. All because you were a tiny bit more cognizant and aware of your surroundings than you were before.

Which brings us to our multiple-choice quiz answer. Why do car owners go to the dealer for service? Because they don’t know any better, and because it’s convenient. Also, if you bought your car new, the dealership almost certainly offered you a free oil change and tire rotation or two when you closed the deal. Sometimes, depending on how naïve you look, they’ll go so far as to insult you by offering services that even Baker from Man vs. Debt could perform on his own. Like replacing windshield wipers, for instance, as if that’s something that anyone with opposable thumbs couldn’t do.

Merchants have been offering “free” goods and services for millennia, and still people get suckered in. It’s not that the merchants are necessarily cheating you, but rather that you need to take into account what they’re selling you beyond the free stuff. Free socks with that new pair of sneakers? Maybe, just maybe, and you’re not going to believe this, Foot Locker factors in the (minimal, to them) price of the socks and still makes a tidy profit off you when you buy that pair of Reebok RealFlex CrossFit Nanos.

Even without the free oil changes, the dealer relies on your presumed comfort level to make you a lifetime customer. The friendly man who sold you the car? There are even friendlier men working at the dealership as service advisors!

Of course they’re friendly, you’re responsible for financing their fishing boats and summer cabins.

We’ve discussed it on this site before, and elsewhere, ad nauseam. Like the time we priced a job that included replacing both sets of front brake pads and the calipers, cleaning the rotors and bleeding the lines. The dealer quoted $871.45. Oops, left my credit card at home. It’s the darnedest thing. How about I bring my car back this afternoon?

The shop down the street offered to do the same job for $398.34.

Only with rare exceptions should you take your car to the dealer. For warranty work, obviously, but beyond that the reasons you should let the dealer touch your car are selected and rare. Resetting the factory satellite radio unit, for instance.

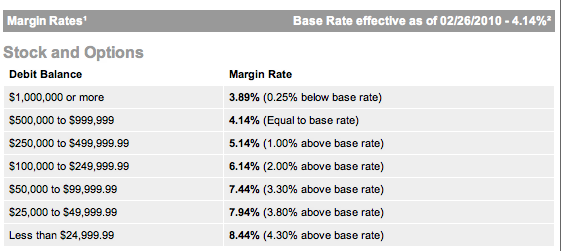

Even the most meaninglessly inconsequential items are cheaper just about anywhere other than your dealer’s service department. Case in point, Motorcraft Part 15K601:

Damn, those internet retailers really are killing Main Street. We didn’t even think about visiting the neighborhood mom-and-pop key fob store.

Once more, repeat after us:

Poor people are poor largely because they choose to be.

It was only a few years ago that “comparison shopping” meant driving across town and burning a day or two to find the best deal. Today, that’s not an issue. While reading this post, there’s nothing to stop you from opening a couple more tabs and finding meaningful savings on your next purchase of whatever. The money you save, you can buy assets with. This is how you get rich. There really isn’t much more to it.

This article is featured in:

**The Carnival of Personal Finance 364: The Art of PF Blogging Edition**