Welcome to one of those rare 1st-person stories in which we give a smattering of detail about our personal financial life, which is comfortable, so that you can apply the decision to your own life and watch the benefits accrue.

Among the houses in the CYC Land Empire, which still totals a few thousand square miles fewer than John Malone’s, is a handsome 3-bed/2-bath number which we rent out in Clark County, Nevada.

(Fun Fact: The home is in Las Vegas, but that’s not the Fun Fact. The Fun Fact is that in the 1990s, and possibly still today, Citibank operated a check processing center and several other concerns on the outskirts of town. Convinced that their clientele were dumb enough to think that monies addressed to “Las Vegas, NV” would somehow end up on a baccarat table or inside a slot machine before finding their way to Citibank, the company used the county name in place of the city identifier. Beyond that, Citibank created fictional towns that people could send correspondence to without fear. Red Rock, NV was one. The Lakes, NV was another. These cities never existed in any form, but the postal service didn’t care as long as you used the right street address and ZIP code.)

In April of 2005 we refinanced the house, which we’d bought a couple years earlier, for $160,000. A couple of paper transactions later – a sale to a trust we own, and then to a limited liability company of which we’re the directors and officers – and the house is now more than ¼ of the way to being paid off. Well, that’s not exactly true. The mortgage term is more than ¼ over – 7½ years out of 30 – but we’ve dented only ⅛ of the principal. Which is how these things work. The portion of the monthly payment that goes to principal accelerates as we get approach the end of the mortgage. Math.

If you remember, 2005 was an awful time to buy a house and a similarly bad time to refinance one. The bubble was about at its limits, a nationwide mountain of unsustainable debt ready to prick it at any provocation. Still, the proper comparison at the time wasn’t to 2008 home prices. (For one thing, we didn’t know what those were going to be.) The proper comparison was to other investments. We had nothing at our disposal that would (almost) guarantee $1200 or so a month in cash flow, so we committed to the house. Which last appraised at exactly a quarter-million, which probably says less about our shrewdness as investors than it does about the appraiser’s love of round numbers.

The current monthly payment is $1078. The house is in a pleasant if not affluent area, with no visible meth labs nor signs of suburban decay. The neighbors are clean and quiet, as best we can tell. In other words, the street started off OK and doesn’t seem to be getting any worse.

ANYHOW…yesterday we received an ominous phone call from someone purporting to be from a bank. “Hi, this is Christina. Please call me back at this number.” She didn’t address the person she was leaving the voice mail for, which seemed suspicious. A few seconds of Googling did confirm that she was indeed a bank employee and not a sophisticated criminal who dupes people into calling them back with their financial information. (We may have been born at night, but…) Then our skepticism made way for good old-fashioned Catholic guilt. “Oh my God, are they repossessing the house?” No, our payment record is perfect. “Sweet Jesus, are they calling because someone hacked into our account and…?” Even if that were true, what could such a person do? Pay off our balance? We’re debtors here. Anyone who impersonates us is going to be impersonating someone with 22½ years of financial obligations.

Or 15 years. When we finally got a hold of Christina, she made us an offer:

Your credit history is perfect. You’re paying too much. If you want to refinance again, we can put you in a 15-year mortgage for only $100 a month more than you’re paying now. It costs $420 to do this. You want me to send you the paperwork?

Yes, you can send us the paperwork.

But no, we don’t want your charity.

Our current rate is 5⅞%. The new one was supposed to be 4½%. The new monthly payment would indeed have been $100 more, but we’d also be cutting 7½ years off our obligation. (Not forgetting the $420 upfront cost, of course.)

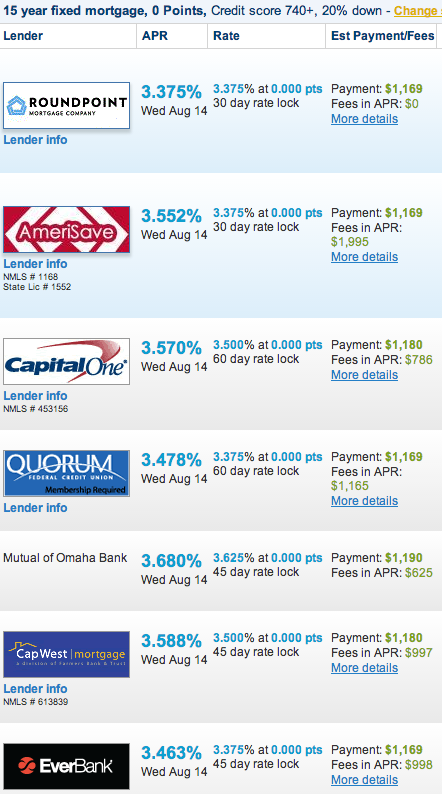

So it’d take 2 years for this to pay for itself, and again, it frees up 7½ years worth of investment potential, new opportunities to take advantage of. If we held onto the house for 2 years and 1 month, assuming the market doesn’t crash again, this would seem like a shrewd move. Except for one thing. Well, 2 things. First, the closing costs worksheet the bank employee sent us used a rate of 4⅞%, not 4½%. Baiting-and-switching us isn’t a good way to start this relationship off. Second, just look at this (changed slightly since we stole created the graphic):

The worst rate listed on Bankrate is 3.68%, that from Mutual of Omaha. With all due respect, we think we’re entitled to the 3⅜% that Roundpoint customers are paying.

Say we hold onto the house for another 5 years. Sparing you the calculations, if we take advantage of the bank’s “generous” offer we’ll have paid down an additional $14,994.89 in principal. We’ll also have forked over an extra $10,504.80 in monthly payments. Is doing this worth $4,490.09, given that it takes 5 years to realize?

No, because there are better offers out there. Paying 120 basis points over market price is insanity. Not quite as insane as staying in our current loan, but at least now we know we have options. In the interests of full disclosure, we’ll shop around and give you our findings next week. And tell you how much we’ll end up saving.