Meet us back here on Election Day 2012, and tell us that “the college crisis” didn’t become an issue in the 33 months since this post appeared.

We’ve already heard how the domestic automotive industry is the unseverable spinal cord of the American economy, and that it’s our duty to our fellow man (if he’s a UAW member) to spend $50 billion propping up this radiant pulsar of American commerce.

In 2008, you had to go all the way down to the presidential candidate with the 5th-most votes (the Constitution Party’s Chuck Baldwin) before finding one who didn’t spout off some variation on how crucial it was to “keep Americans in their homes”, even if those Americans borrowed too much money and assumed that a steady increase in their homes’ values was a cosmological constant.

And as we heard from a prior presidential administration, doling out 700 billion taxpayer dollars (that’s $233 for each of us) was necessary to keep some of the nation’s largest investment banks in the business of lending money, otherwise “the whole system would collapse”, which presumably means we’d be reduced to collecting animal pelts in exchange for our mp3s and bedroom linens. “I’ve abandoned free-market principles to save the free market” was the quote. To paraphrase a ‘60s-era t-shirt and bumper sticker, that’s like (having sex) for virginity.

Meet the next bubble – post-secondary education.

The problem is this: despite the recession, our society has gotten so absurdly rich that today, young adults loaded with potential can postpone any worthwhile work and ring up debts in the process, all in the name of getting an education. How “education” became more important than “productivity” or “fulfillment” or “not being a drain on society” is unclear.

Yes, we’ve all seen the studies say that college graduates make more money than high school graduates – somewhere around $15,000 annually. This is a mantra people take to heart without examining in any detail. It sounds logical, as many jobs require applicants to have college degrees. But like many bromides that attempt to persuade you of a fact in as pithy a fashion as possible, the $15,000 allegation tells only a minute part of the story.

The median salary for petroleum engineers is around $108,000. For a physician who’s been out of school for a couple of years, it’s reasonable to assume he’ll make anywhere from $170,000 or so for a pediatrician to more than $500,000 for a neurosurgeon.

What about philosophy graduates? English majors? People who think a sociology degree is worth anything? We don’t have figures for them, because the Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t list “barista” and “street musician” as employment categories. Sure, the average college graduate makes a better salary than the average high school graduate. But the average college graduate is part doctor and part engineer. The students who major in the hard sciences are dragging the political science and journalism majors up with them.

This statistic puts the cart before the horse, and puts passivity ahead of activity. For many college graduates who inherently know, just know, that the last 4 or 5 years were worth it, they assume that that diploma is the negotiable equivalent of a $15,000 annuity. God forbid they actually go to the trouble of applying it.

The University of Hawai’i’s spring semester enrollment is up 9.4% over last year. Instead of working harder than ever to find jobs in a weak economy, people are willfully deferring life – and paying money they don’t have for the privilege. And it’s not like UH is creating more engineers and scientists. A college vice president says “They tend to be all over the place. We have graduate students seeking their master’s, students in areas where there’s a shortage, such as teaching, nursing and social work, and business is popular, but so is psychology.”

And parents, don’t leave the room. We’re not done with you, either. The following is your financial obligation to your kids: food, clothing and shelter until they reach the age of majority. That’s it. No one owes anybody a college education, just like no one owes anyone a house or regular doctor visits. Your kid is far better off becoming a welding technician straight out of high school than wasting four years earning a degree in gender & women’s studies and beginning the income-earning years tens of thousands of dollars in debt. Economically speaking it’s better yet that he become a neurosurgeon, of course, but the world still needs welding technicians.

On the macro level, everyone from your neighbor to the president is talking up post-secondary education. The neighbor does it because he doesn’t know any better, the president for the same reason any elected official advocates anything.* The talking points are familiar: the next generation of Americans needs to be prepared in an ever more competitive world, education is a fundamental right, do you really want America to be a nation of blathering idiots, etc., etc.

This obscures the truth by shrouding it in catchphrases. This may be indelicate, but that doesn’t make it false: things cost money.

An investment, even in one’s own education, is a deferment of resources for an expected return. The majority of college kids don’t know a damn thing about what they’ll do when they get out of college. Therefore for them college isn’t an investment, it’s an expense.

That’s not to say that finishing high school is all you need to do to enter the workforce with a minimum of debt. There’s still a thing called motivation. Completing school, at whatever level, shows that you had the diligence to sit quietly and take some tests. There are a million ways to earn a respectable living out of high school – carpentry apprentice, garbageman, junior lab technician – but taking a random selection of undemanding college courses is not one of them.

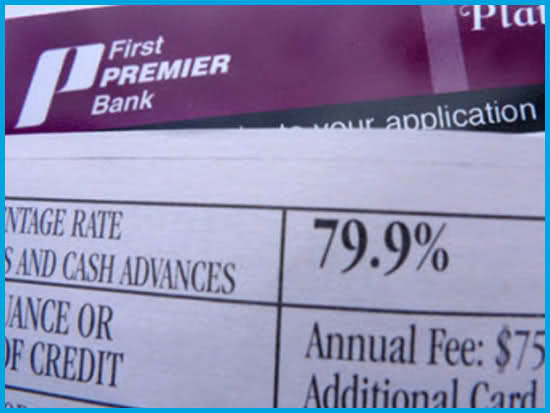

Yet the government, true to its misguided principles, subsidizes education. President Obama proposes, in public and behind a live microphone, that no college graduate should have to fork over more than 10% of his income in student loan payments. This is what commerce has come to in 2010 – the terms of an agreement are dictated by future occurrences. Of course no one wants to pay 10% of his income on debt obligations, or on anything else for that matter. Not that 10% is an insurmountable number, but if the government mandates that it’s too high, pretty soon people will agree that it is too high, and that no $40,000-a-year junior account executive should suffer the inconvenience of paying more than $333 a month toward her student loans.

It gets better. (Or worse, if this kind of thing bothers you, which it should.) The president adds that student loans should be forgiven after 20 years – 10 if the borrower “enters into a life of public service.”

His definition of public service goes beyond Green Berets and SEALs. Say you want to take your forestry degree and be a National Park Service ranger, which offers room and board and pays $35,000 annually. Thanks to the time value of money, you’d be getting close to a complimentary education while doing nothing that makes a measurable impact on America’s gross national product.

But after the 10 (or 20) years, the unpaid part of your education doesn’t suddenly become “free”. Services were still rendered, the college still paid its professors and maintained its classrooms and grounds. Who makes up the difference? (Hint: the same generous soul who already bailed out Chrysler, GM, AIG, Lehman, your deadbeat neighbor who didn’t know how to sign a loan document, etc.)

People respond to incentives. If the government declares that the price you pay for your education will be arbitrarily lowered, more people will go to college. And earn useless degrees. And take their sweet time paying them back, if at all. But at least our elected officials can brag that a higher percentage of Americans go to college than do the Irish or the Icelandic.

*To get elected. (And in this particular case, to distract attention from more pressing matters, such as the ever-closer destruction of Social Security.)

**This article is an Editor’s Pick at The Best of the Best in Money and Personal Finance #12**