The Dow. Or, in metonymic fashion, simply “the market”. The single quantity most identified with the strength or potency of the economy, particularly its investing arm. We’ve discussed before what exactly the Dow Jones Industrial Average is and how to calculate it, but that was 4 years ago and it’s time for a freshening.

In one sentence, if you’re too lazy or burned out to read the linked article above: Add the stock prices of 30 particular large companies, multiply the sum by a constant, and there’s your Dow index. Mindlessly simple, and either in spite or because of that it’s managed to burrow itself into the collective consciousness. The companies have changed throughout the years, U.S. Leather having less impact on the economy today than it did in 1899, but here are the 27 oldest constituents of the Dow:

| 3M | American Express | AT&T |

| Boeing | Caterpillar | Chevron |

| Cisco | Coca-Cola | DuPont |

| ExxonMobil | General Electric | Walmart |

| Home Depot | Intel | IBM |

| Johnson & Johnson | JPMorgan Chase | McDonald’s |

| Merck | Microsoft | Disney |

| Pfizer | Procter & Gamble | Travelers |

| UnitedHealth Group | United Technologies | Verizon |

Earlier this month, the 3 remaining slots were occupied by Bank of America, Alcoa, and Hewlett-Packard. Last year the Dow traded out one of its components for another, and this is the first time in 9 years that it’s traded out 3 simultaneously. We’ll get to the newcomers in a minute.

Bank of America, as you may remember from our haranguing of a couple years back, received a direct $45 billion in taxpayer cash, and $5 billion more via equally culpable straw purchaser intermediary American International Group to avoid what 2 presidential administrations feared would be the collapse of the economy. We weren’t close to having that happen, and the bailout did thousands of times more harm than good, but Bank of America has a more effective public relations department than we do. 6 weeks after the cash infusion, B of A stock hit a nadir of $3.14. Within a year the stock price had sextupled, leading B of A management to issue pronouncements; of perfunctory thanks to the helpless taxpayers, and of the promise of happy days ahead to investors and borrowers. Long story short, by the end of the next year the stock had again lost 2/3 of its value. A consistent non-performer drags the value of the index down, so Dow Jones & Company said “enough” and went looking for suitable replacements.

Same deal, to a lesser extent, for Alcoa and Hewlett-Packard. The former is profitable but dwindlingly so, and revenue is down year-to-year for the first time in a long time. Alcoa is an acronym for Aluminum Corporation of America, and aluminum prices have been dropping steadily for the last 2 years. Alcoa isn’t diversified enough to make up for the commodity price drop, and so it did do the Dow adieu.

Did do the Dow adieu. Did do the Dow adieu. In other news, the 6th sick sheik’s 6th sheep’s sick.

Finally, the titan-cum-laughingstock Hewlett-Packard. For those of you either too young to know or too well-balanced in your daily lives to care about this stuff, Bill Hewlett and David Packard were the original Jobs & Woz. H & P started their company in a garage in Palo Alto, the Steves in a garage in Los Altos, 8 miles away.

But a lot has changed since 1939. By the 2010s, Hewlett-Packard was making mistakes almost for the fun of it. The company spent $1.2 billion to buy Palm, and basically wrote the purchase off a year later. They hired an overmatched CEO who didn’t even last a year. He authorized the purchase of Autonomy, and if you think the Palm purchase was stupid at least Palm didn’t publicly overstate its value by $9 billion. Yeah, that was another writeoff. Hewlett-Packard stock free-fell last fall, bounced back this year (doubled, in fact), but that wasn’t enough to keep it in the Dow.

The replacement stocks fit the index as well as any, given the Dow’s implied goals of reflecting the diversity and breadth of the economy. The committee traded out a tech company, a mining company and a bank and replaced them with…a shoe company and 2 more banks.

Notice something about the list of 27? Relatively few of them are full-on consumer companies, selling something you can buy in a store. Thus Nike joined the mix. Not coincidentally, Nike stock is at an all-time zenith. Revenue is growing – arithmetically rather than geometrically, but Nike has been around for a few decades. Add healthy profit margins and a price/earnings ratio with room for growth, and Nike was an easy choice.

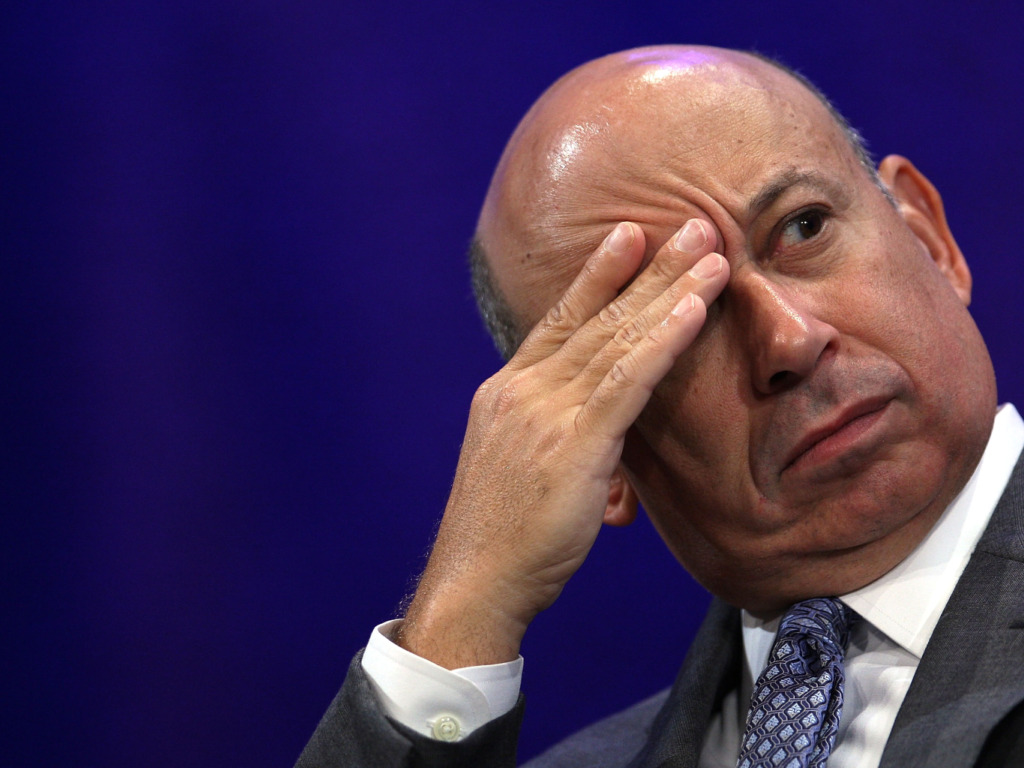

Goldman Sachs, profiteers of the 2008 mortgage crisis and beneficiaries of the infamous Troubled Asset Relief Program, replaced Bank of America. An exchange of scoundrels? Perhaps, but the former’s financial statements are far more attractive than the latter’s. Goldman Sachs’s earnings per share is at a record high. Also, it’s the most juiced company in America. Its CEO seems to spend more nights at the White House than Michelle Obama does, and the list of recent Treasury Department upper-level hires reads like the 2002 Goldman Sachs internal phone directory.

That leaves Visa which, curiously, began to trade publicly only in the spring of 2008. (Prior to that Visa was more an agglomeration of companies, more of a “membership association” than a standard stock issuer.) At its initial public offering the stock traded at $44. It’s now within a gallon of gas of $200, and the company enjoys a market capitalization of $125 billion. (Fun Fact: Visa cards debuted in 1958, under the name BankAmericard. A service of…Bank of America. B of A licensed the card to other banks, and by 1970 had effectively ceded control to the entity that would become Visa.)

How does this affect you, the ordinary investor (assuming you’re an ordinary investor)? Minimally, unless your investments’ value derives from the value of the Dow. Or, of course, if you’re long into any of these 6 companies. If your mutual funds are tied to an index, chances are pretty good that it’s the 17-times-broader S&P 500, whose makeup remains unchanged.