(This post contains repeated references to video games, a subject we know nothing about. Forgive us in advance if our descriptions are stilted, ignorant, or both.)

A few days ago, Boston Red Sox owner and investor/former commodities broker John Henry bought the Boston Globe for $70 million. The paper sold for $1.1 billion 20 years ago, meaning it’s lost 95% of its value. Why would a rational, profit-maximizing businessman buy into a dying industry, even at what seems to be a low price? Not a rhetorical question, especially since newspapers are notorious for being operated by people not known for their aptitude with a dollar.

Henry didn’t buy a newspaper. He bought some sweet real estate, with a disposable information delivery system thrown in. (We don’t mean that the newspapers themselves can be discarded. We mean the very apparatus that creates and distributes the papers is ancillary to the deal.) The building that houses the Globe could sell, today, for at least $5 million more than Henry paid. (Granted, that number comes from the Globe‘s crosstown rival. But, as we said in high school debating class, still.)

The additional $1.03 billion in value that the Globe (oh, enough with this pretentious italicizing of newspaper names, like they’re somehow deserving of a higher status than other commercial enterprises aren’t) commanded in 1993 was illusory. Today the paper and what’s printed on it, and even its website, have negligible worth. All that matters in this transaction is the commodity that, as Will Rogers pointed out, “they ain’t making any more of.” But “Local Tycoon Buys 135 Morrissey Boulevard” isn’t much of a headline. (On a side note, Henry insisted that the previous owners – The New York Times Corporation – hold on to $100 million in pension liabilities. Which they did. If business deals had referees, this one would have called a TKO several rounds ago.)

So the paper was the marquee acquisition, but as such trades go, strictly a throw-in. The Mike Krushelnyski of the deal. Right now you’re saying to yourself, or possibly aloud, “Why are these idiots wasting my time with a story about a billionaire’s latest endeavor? This has no bearing nor application to my life.”

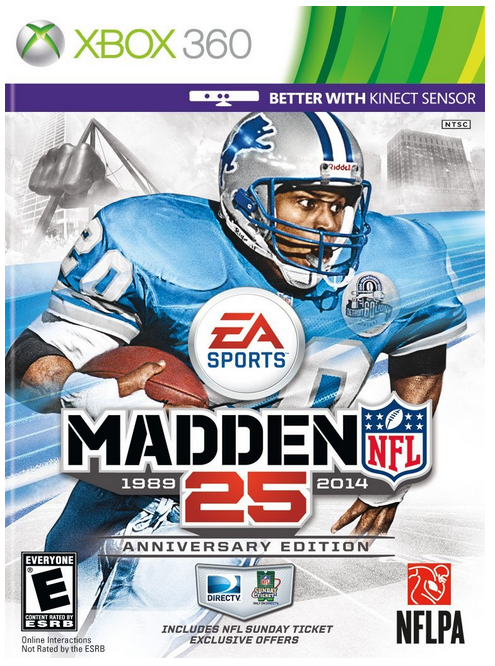

Pish. Also, posh. Earlier today, the CYC principals spent $100 and became proud owners of their first-ever video game: Madden NFL 25. Specifically, Madden NFL 25 Anniversary Edition. For Xbox. We weren’t daunted in the least by the reality that we don’t own an Xbox. Nor would we know what to do with one if we did. We do, however, enjoy watching our de facto national pastime. And here’s what prompted us to buy a product we have no utility for: said edition of Madden comes with a code good for a season of NFL Sunday Ticket Max. We bought a retinue of NFL games and got a superfluous video game for good measure.

(If you know what NFL Sunday Ticket is, skip this paragraph.) If you’re European, a fan of Broadway, or both, we can explain that NFL Sunday Ticket is a TV subscription package that lets people watch football games they’d normally be unable to. The National Football League plays 80% of its schedule on Sunday afternoons (and mornings, in the time zones that CYC headquarters shuttles between.) There are 32 teams in the league, which means that often 4 and sometimes as many as 10 games are going on simultaneously on Sundays. With the NFL knowing the value of scarcity, and the human head having 18 eyes too few to take in all the games anyway, viewers who rely on basic over-the-air broadcast TV have only 1 or 2 games available in their particular region at any given time. (Said Sunday games are broadcast on CBS and Fox, which are available to 99% of American homes, without charge.) If you live in Phoenix, you’re probably not going to get to see the Miami Dolphins play. If you live in Jamestown, North Dakota, the Houston Texans are often going to be nothing more than a rumor. But Sunday Ticket changed all that, making theoretically any game available to anyone willing to pay to watch it.

Sunday Ticket Max, as distinguished from Sunday Ticket, also includes the glorious Red Zone Channel. It features live cuts to the most crucial moments of each game, non-stop, with no commercials. Which is so amazing that it warrants both italicizing and boldfacing. The catch is that Sunday Ticket is only available via DirecTV, a company we happen to patronize already. And as long as we’re listing catches, this deal is only available via Amazon. And EA Sports is making only 100,000 copies of the Anniversary Edition.

Sunday Ticket Max normally costs $300 a season. And unlike its unMaxed counterpart, allows you to watch games on iPads and stuff.

As best we can tell, the video game without the DirecTV code – the non-Anniversary Edition – will sell for somewhere around $55 on eBay. So for $45, we’ll be getting $300 worth of beautiful, bellicose, brain-deadening NFL action. Barely a dollar a game. (Also, CYC’s Winter Headquarters are in a condo complex, one whose cable package bafflingly excludes The NFL Network. Which meant that watching Thursday night games, shown exclusively on The NFL Network, required us to visit the local bar and inhale smoke. No more, given that Sunday Ticket allows us to watch Thursday night games too.)

Today’s lesson? When you reach into your wallet, remember that ultimately you’re not buying a “product” – a good or a service. You’re buying a benefit. The old advertising axiom fits perfectly here: “People don’t want soap. They want clean hands.” The soap is secondary. In our case, the video game was secondary. Even better, we can sell it, let someone else enjoy its benefit, and extricate said benefit from the only one we care about – the ability to watch football at our leisure.