This post doesn’t have a lot to do with personal finance, but we did the research and needed to present it somewhere. Just as George Will takes a break from his political columns to write an annual column on baseball, consider this our indulgence. Plus you’ll learn something. If you know the rudiments of sports gambling, start reading again where it goes red.

Like all wagering, sports gambling is largely stupid from the bettor’s perspective, a way for the book to earn a 4.5% return on your money in the length of time it takes to play a football or basketball game. The most common bet in those particular sports involves invoking the pointspread. You don’t bet on a team to win, you bet on a team to cover said spread. For instance, on Thursday the Oklahoma City Thunder and Miami Heat will play Game 5 of the NBA Finals. Miami is a 3½-point favorite, meaning that if you bet on Miami, they need to win by at least 4 for you to collect. If they win by less than 4, or lose, you lose too. Conversely, a bet on Oklahoma City means they can’t do any worse than lose by 3. If you bet on “Oklahoma City plus three and a half”, to use the jargon, you’ll be ecstatic if they win, and no less happy if they lose by up to 3. In short, when the game ends, we subtract the point spread from the favored team’s score for betting purposes.

Of course, many games’ outcomes are determined well before the final buzzer. The point spread is the means by which a game that threatens to be uncompetitive can attract a bettor’s interest. Say San Antonio, the team with the regular season’s best record, is favored to beat historically abysmal Charlotte by 20. But if San Antonio is leading 121-100 with :30 to play, even though the game itself was long ago decided, every wager is still very much alive. If you had San Antonio -20, only to see Charlotte hoist up a meaningless basket at the end of the game, you’re going to be homicidal. And if you took Charlotte +20, you’re going to be overjoyed. That’s an example of the infamous backdoor cover, which can turn otherwise rational sports viewers into frothing lunatics. The ultimate backdoor cover happens when time expires just as the final shot goes in.

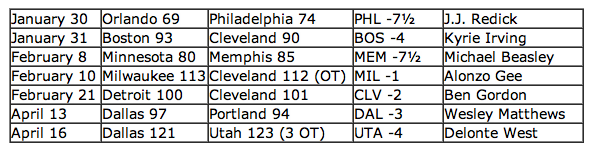

Which brings us to our study topic. Oklahoma City’s James Harden hit a buzzer-beating backdoor cover earlier in the playoffs, which made us wonder how common they are. We went through all 990 regular season games, looking for last-second baskets that didn’t affect the game’s outcome but that did affect the line. We found 5 that turned a wagering loss into a win (or vice versa) and 2 that turned the game into a push (game lands exactly on the spread, all bets refunded.) All the buzzer-beaters were 3-pointers, and all were hoisted up by the losing team:

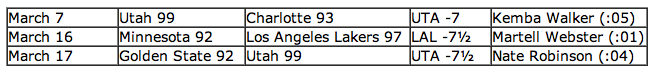

There were 3 more that weren’t shot at the buzzer, but were close enough. Again, all were 3-pointers shot by the underdog:

Is this just esoterica, or are there any practical lessons to learn from this? No and yes.

First, understand that the sports books’ job is not to predict who’s going to win and by how much. Rather, their job is to place the pointspread at the precise location where they estimate they’ll be as much money wagered on one side of the game as on the other. From their perspective, in a perfect world tomorrow night’s game would have exactly $x bet on Miami and exactly $x on Oklahoma City. That way, the books would guarantee that they’ll receive their standard 4.5% cut on the game’s handle, regardless of who wins.

What, you thought it worked differently? You thought sports books try to determine who’ll win a game, cross their fingers that people will bet on the other side, then hope to collect all the money? Of course they don’t do that, that’d be gambling. And if anyone knows that gambling is stupid, it’s casino executives. To quote the tobacco company CEO, “No thanks, I don’t smoke. That stuff will kill you.” They’d much rather take a guaranteed 4.5% return than virtually no chance at a 100% return.

That being said, a team that’s ahead and is just waiting for the game to end isn’t going to put up pointless shots. That’d be rubbing the opponent’s face in it, kind of. On the other hand, the opponent wants to save face and keep things as close as possible if the opportunity presents itself. Even if “close” has little meaning: losing a game by 7 isn’t any different than losing by 10. A team that’s up by an insurmountable amount isn’t going to bother contesting the opponent’s desperate, low-percentage shots. The leading team’s attitude is go ahead, have at it: just make sure you use as much of the shot clock as possible, so the game isn’t unnecessarily prolonged and so we can all go home.

Thus, taking the underdog is ever-so-slightly a better play than taking the favorite. Enough that it made a difference in around 1% of games this year. Favorites never cover on last-second shots that don’t affect the outcome of the game, while underdogs sometimes do.

That’s if someone has a gun to your head and order you to gamble. Voluntary gambling remains ludicrous.