If you work for a living, especially if you do anything that gets your fingers calloused or makes you sweat, it’s easy to wonder what a financial services firm does aside from employ well-dressed people to shuffle paper.

Goldman Sachs is a financial services firm, one of the world’s biggest. An investment bank, if you want a slightly more limiting but descriptive term.

You have a neighborhood bank – e.g. Chase, SunTrust, BB&T. You deposit your paychecks there, withdraw cash, earn interest, maybe borrow money to buy a house or start a business. The bank makes money by charging more interest on its loans than it pays out to its accountholders.

Investment banks such as Goldman Sachs have better, more lucrative ways to occupy their time. Say a medium-to-large firm wants to buy another, or sell itself or a piece. The firm hires an investment bank to value the assets and liabilities involved, help with pricing and look for contingencies that the parties involved in the transaction might have missed (e.g. determining the rightful owner of certain assets, making sure that a legal transgression doesn’t render a transaction void.)

Investment banks do more than that, too. You probably know that some companies issue bonds to raise money – in other words, they borrow it from whoever’s willing to lend it. You can buy a bond issued by Johnson & Johnson for a little over $100, and receive 4.061% annually until the bond matures 13 years from now. It’s an investment bank that underwrites that issue of bonds – figuring out how much Johnson & Johnson should borrow and what rate to offer, then selling the bonds to brokerage houses that will in turn sell said bonds to their clients. The same goes for issuing stock, only in that case the investment bank helps determine the initial market price and the volume of the issue. After that point market forces (and in 2010 America, governmental suasion) take over.

Banks like Goldman Sachs also exchange currencies, millions of dollars (or pounds or pesos) worth at a time, to keep their clients liquid and protect them from inflation in whichever nation they happen to be conducting business. Of course, said banks take a cut. An investment bank’s clients also trust it to buy equities, bonds and commodities on its behalf, putting the clients’ assets to (presumably) efficient use instead of just having them sit around in cash that doesn’t earn interest.

Investment banks also create and manage mutual funds and pension funds, pooling different investments to create a meta-investment that you can buy into and hopefully preserve your assets in. Investment banks also manage assets for foundations, colleges and universities, and rich individuals and families. And occasionally, an investment bank will invest in a business itself. In Goldman Sachs’ case, everything from Las Vegas casinos to Chinese meat processing.

So while what investment banks do isn’t as tangible as what engineering firms or agribusinesses do, investment banks still serve a clear purpose that helps resources find their most efficient use, which is the whole point of capitalism and progress. This takes skill and experience. You wouldn’t hire a bunch of teenagers and pay them minimum wage to underwrite your next bond issue.

Investment banking is intellectually challenging, risky, and should offer commensurate rewards. And when the bankers make the wrong decisions – charging too low a rate of interest, buying a security whose price then tailspins – they should eat the losses.

Should.

In 2007 Goldman Sachs made huge profits on mortgage-backed securities, the investments made up of mortgage debt pooled and sold with the promise of interest. Lots of people defaulted on their mortgages, which made the mortgage-backed securities lose money. A couple of Goldman Sachs employees predicted this, sold short all the mortgage-backed securities they could find, and the company profited while other Wall Street firms got burned. However, Goldman Sachs created securities of its own that were dubious and difficult to value – including several whose underlying investment was home equity loans, which are always at a relatively high risk of default. Goldman Sachs stock went from a high of $234 in October of 2007 to $52 in November of 2008.

Around the same time, you helped out by buying $10 billion worth of Goldman Sachs stock. Because it’s your federal government’s job to keep investment banks viable, for some reason.

Greece is bankrupt, or close to it. For 11 years Goldman Sachs helped the Greek government fudge its numbers, allowing the nation to pile up debt that it now has to refinance to the tune of $11,500 per citizen. In 2009, Goldman Sachs received cash from U.S. government ward AIG in return for even more dubious securities. That’s cash that originated with American taxpayers. Goldman Sachs sold further securities (collateralized debt obligations) to investors, then bet short against them, the equivalent of Los Angeles Lakers owner Jerry Buss wagering on the Utah Jazz in their current NBA playoff series against the Lakers (which would pay 17/4 had he wagered before the series began.)

It’s those collateralized debt obligations that are the primary reason why Goldman Sachs is in the news. Goldman Sachs hired an independent firm (ACA) to review them, but allegedly never informed ACA about a hedge fund (Paulson) that wanted to short the collateralized debt obligations. Which would be fine, except Paulson helped select the underlying mortgages. Continuing with the Jerry Buss analogy, it’d be as if Buss hired a new general manager to release his entire starting 5 of Kobe Bryant, Pau Gasol, Ron Artest, Derek Fisher and Andrew Bynum, then signed 5 random New Jersey Nets to replace them.

The 2 Dutch firms on the other side of what became a billion-dollar loss are understandably miffed, and have taken their case to the Securities and Exchange Commission. Goldman Sachs argues that hey, we just bring buyers and sellers together and what happens after that is up to the market.

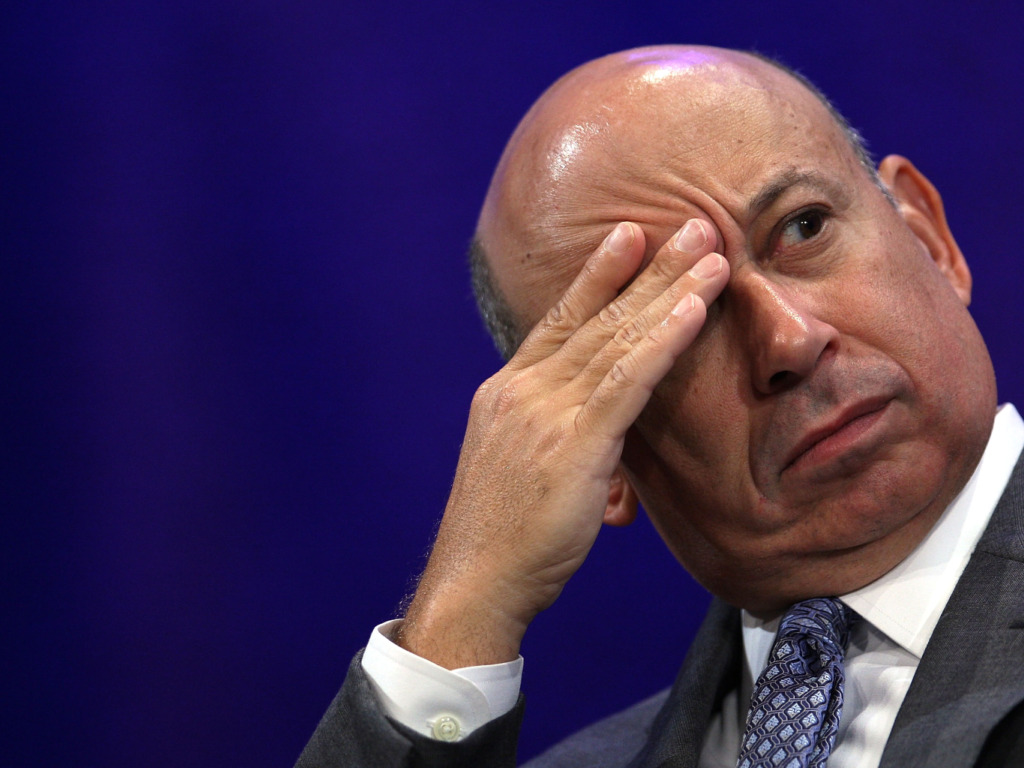

In a completely unrelated and independent development, Goldman Sachs employees and family members contributed more money to the president’s election campaign than any firm but one. Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein has visited the White House 4 times, which is 4 times more than you. Enjoy your work week.