We’ve never done a post on The Oracle of Omaha, which makes us unique among personal finance blogs. We also didn’t misspell his name as “Buffet”, which also makes us unique among personal finance blogs.

Yes, he’s the greatest investor of all time. No one disputes this. The problem is when he starts talking about topics he either knows nothing about, or is being deliberately obtuse about. Amassing wealth doesn’t make you an authority on every subject. Case in point, his recent lament about taxes.

Buffett wrote in The New York Times that the current progressive tax system in this country, in which rich people bankroll most everything, just isn’t progressive enough. He pointed out, yet again, the absurdity of his secretary paying a higher percentage of her salary in taxes than he does.

Summarizing, Buffett claims that at least one of his employees allegedly pays an effective tax rate of around 41% on income, while Buffett himself pays 17%.

First, the former claim is a lie. The highest marginal tax rate in this country isn’t even 41%, let alone the highest average tax rate. The highest marginal tax rate is 35%, and given the income level at which the IRS administers it, to pay an effective tax rate of 35% you’d have to make $6 million a year.

So Buffett’s not comparing himself to the woman who answers phones at Berkshire Hathaway. He’s comparing himself to a manager who makes a higher salary than almost everyone in America, even more than your average NBA or major league baseball player.

We’re giving Buffett the benefit of the doubt here, assuming that he meant 35% instead of 41% even though those numbers are easy to distinguish. No one knows where he got the 41% figure from.

Furthermore, that 35% maximum rate is on taxable income. Anyone who’s ever filled out a 1040, or had someone else do it, knows that taxable income is considerably less than total income. There are these things called deductions and credits, which Buffett is presumably familiar with (and which any manager who makes $6 million a year must be familiar with, too.)

It makes for a great class warfare talking point: every dollar that I fail to make is somehow some richer person’s doing. And who better to inspire envy among the poor salaried millions than a tycoon who’s finally seen the error of his ways?

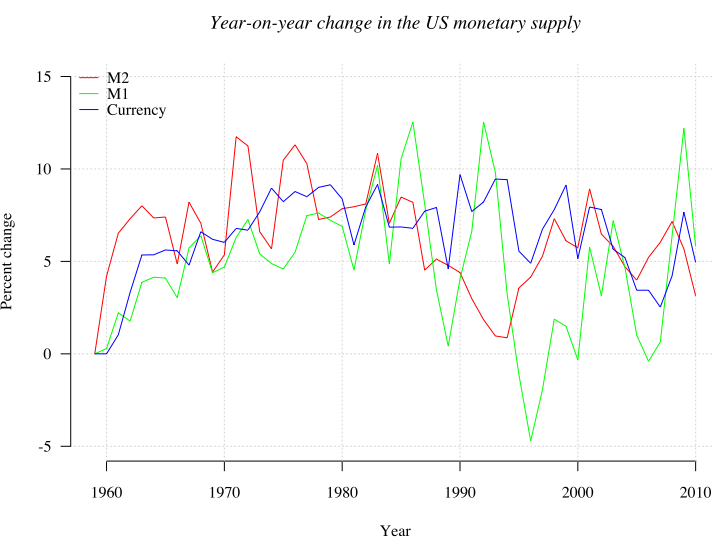

Buffett – and we salute him for this – has spent a lifetime earning money via capital gains, rather than salary. Do we think this is a good idea? Hell, we wrote a book about it.

Capital gains are taxed at lower rates than salaries are. The people who write the tax code, and make it the most cumbersome and impenetrable thing on the planet, ensure this. Of course they do. Legislators write the code to accommodate and exploit this, because they derive most of their income through capital gains.

Let’s assume that Buffett indeed has employees who are paying twice the proportion of their income in taxes as he is. What’s the fairest way to make things fair? Again, multiple-choice.

- Further soak the rich.

- Get government’s foot off the throat of the poor.

Raise the rich people’s taxes to make things even, or lower the poor’s? Rich people seem to enjoy being rich. Why not reduce rates on the salaried masses to put them in line with whatever Buffett’s definition of “rich” is, instead of the other way around? Instead of creating prosthetic limbs for amputees, Buffett wants to break the right arms of the able-bodied.

The reactionary answer is “Because it’ll reduce much-needed tax revenue.” It wouldn’t. People respond to incentives, and will have incentive to work harder, longer hours if they get to keep more of what they make. When I can keep 84¢ of my next marginal dollar, there’s a better chance I’ll work for that dollar than if I only get to keep 67¢.

It’s the height of arrogance to complain about the tax system not because it hurts you, but because it benefits you. Especially when there are so many ways for Buffett to fix this perceived injustice. Sure, he could cut Washington a check for whatever amount he feels he should be paying. He could increase his employees’ pay enough to offset any tax advantage.

Or, and this is the least likely of the three, he could rework the dividends that flow through his corporations so that he could receive all his income as salary, rather than capital gains. The chance of this happening is roughly equivalent to the likelihood of Buffett running a 4-minute mile.

————————-

We’ve been pushing the concept of a diagonal tax since we were old enough to understand the concept. Everyone gets a basic personal deduction – say $20,000 – and pays some percentage – say 17 – on the rest.

The guy making $6 million would thus pay 16.94% of his income in taxes. The guy making $30,000 would pay 6% of his income in taxes. The guy whose net worth increases $10 billion in a year would pay 16.99997% of his income in taxes.

People who want to soak the rich should love this system. It treats the rich and the hyper-rich almost identically, biting them almost 3 times as hard as the working stiff, relative to what all three make. If that’s not enough, just manipulate the deduction and percentage numbers until it all makes sense.

**This article is featured in the Yakezie Carnival-October 2, 2011 Welcome Fall Edition**